Introducing Webtendo — open source, multiplayer, in-person game platform

11 Jan 2017Inspiration

Check out my Medium post.

Implementation

On a laptop, a user visits https://webtendo.herokuapp.com and selects a game as the host. On an Android phone, users can visit the same site and select the same game as a player. On iOS, players can download from iTunes. If on the same wifi network, the server automatically determines the room name. After a few seconds everyone connects and can start playing!

To support the broadest range of games, latency between the controllers and the host needs to be minimal, preferably below 30 ms, which is the limit of human perception. So for the transport layer WebRTC seemed to be the natural choice. WebRTC allows devices to communicate on the shortest possible network path between them, even if there’s NAT or firewalling in the way. It’s supported in Chrome on Windows, Mac, and Android, but unfortunately not on Chrome iOS (more on that below). However both iOS and Android have native WebRTC support.

In my tests using Chrome 54 on a Mac and Chrome 54 on Android on the same wifi network, I saw round trip times of about 12 ms, though this spiked much higher if the device was not active. This was the first hint that building a high quality platform might be viable. The codelab and most online resources focused on transmitting realtime audio and video rather than data, so getting an absolute minimum example going was an exercise in chopping down and modifying the examples on the net to their minimum possible.

We also want cross platform support, so developers can reach the largest potential audience without extra effort.

iOS support — learn once, write everywhere

Check it out on iTunes! As I mentioned, iOS browsers don’t support WebRTC, so I needed a native app that would

A few years ago I spent months fighting with PhoneGap/Cordova. I loved how fast I could iterate and test suite execution speed, but at the end of the day the platform itself was too buggy. When we launched, users complained of random network disconnects even when other apps were chugging smoothly. It was hard to follow native UI paradigms. Eventually I bit the bullet and rewrote everything natively on Android, swearing never again to put so much energy into a platform not proven to work at scale.

Fast forward to spring of this year and all my dev friends are talking about React Native, and how magical it is to be able to use all our JS tooling, but still write native apps. It seemed too good to be true, but as I tried it in exploring a side project it turned out to be a wonderful development experience. It has its quirks, but hitting save and seeing the changes almost instantly on the real device is worth it. We no longer have to compromise the dev experience in favor of the user experience.

That said, React native isn’t really built to share code across vanilla React and React Native (otherwise its slogan would be “learn once, write once”), and on top of that I didn’t want to tie developers down to a single layout engine. Maybe someone will make a game in WebGL, another in Canvas, and another in ThreeJS. So I made an semi-awful hack where the transport layer, which doesn’t work in iOS web, is in React Native, and everything else is a webview in React Native. There’s some tricksy bridge code that allows the webview to talk to the native environment and a small cost for serializing and deserializing the JS, but in practice performance is unaffected!

// Connect to the signaling server if we have webrtc access.

let socket;

try {

new RTCSessionDescription();

socket = io.connect();

attachListeners(socket);

} catch (e) {

console.log('No WebRTC detected, bailing out.');

setTimeout(() => {

try {

WebViewBridge;

} catch (e) {

console.log('Dis don look like ReactNative...');

alert('This browser is not supported. Please use Android Chrome or iOS native app.');

}

}, 500);

}

The first try statement will bail out before it establishes the socket connection if it can’t find WebRTC. The second try statement will bail out if it can’t find the WebViewBridge after half a second, since it takes some time for the bridge to get injected. This means we’ll bail instantly on a native client, but not throw the alert unless we’re in an iOS browser.

Luckily I was able to copy over the transport code with just a few small tweaks, and in the future, thanks to Babel transpilation, I intend to reuse the code entirely.

dev/prod config

Another wrinkle is that since React Native doesn’t give the user a URL bar to edit, development builds need to know to use localhost and prod needs to know the public URL. I was surprised this isn’t baked into React Native, since dev vs prod is a part of other frameworks like NPM. But using luggit/react-native-config I was able to easily and readably reference config. In index.ios.js

import Config from 'react-native-config'

var socket = io.connect(`ws://${Config.SIGNALING_SERVER_URL}`, {

...

and then in .env, SIGNALING_SERVER_URL=localhost:8080 and in .env.prod, SIGNALING_SERVER_URL=webtendo.herokuapp.com.

Webpack and ES6

As my friends started making games on the platform, the vanilla HTML5 project structure started causing pain. Which JS files should be imported? What is the public interface for each? Can we have optional typing? What about classes? Etc.

I started out trying to use SystemJS but it was a nightmare. I kept getting strange errors, and in general there was just too much magic. How did the files get generated? Where were they coming from? How do I modify the behavior? Eventually I threw it out and switched to Webpack.

I had heard bad things about Webpack, and nearly all the examples I could find online were too simple or too complicated. Starting simple, however, I appreciated the relative lack of magic in the explicit config and presence of a bunch of features I needed, like transpilation, source-maps, rebuild-on-save, and module loading.

Server

I think full-stack developers underestimate the cost of switching languages between frontend and backend. I got used to this, having done Java, Python and C++ backends, and Javascript and Android Java frontends. Being able to use Javascript everywhere has been unexpectedly lovely. I can use the same editor (Emacs), the same devtools (Chrome/Electron), and the same package management (NPM). I don’t mix up commands and syntax anymore. I looked into serving performance, and it’s not terribly different even between C++ and JS. So, NodeJS it is.

WebRTC allows client-to-client communication, but those clients still need a way to find each other across the vast internet. For this I made a signaling server. ExpressJS seemed too heavyweight a framework for this, so for maximum simplicity I decided to go with entirely static file serving and Socket.IO for high performance, cross-platform transport. Compared to my experience setting up HTTP servers in the past, this was a breeze, and far more powerful.

For example, for a client-to-client message relay, it’s just

let clients = {};

io.sockets.on('connection', function(socket) {

clients[clientId] = socket.id;

socket.on('message', message => {

io.to(clients[message.recipient]).emit('message', message);

});

});

When one machine can’t hold everyone, we can easily plug into Redis and shard.

Room names

A common annoyance with the WebRTC demos I tried was entering a room name, which was typically a random string. On a laptop it’s sort of reasonable to copy/paste this, but on a phone it gets annoying, especially with autocorrect. So I used jjt/hashwords to generate a deterministic, human readable room name from the user’s external IP address.

const hashwords = require('hashwords');

const hasher = hashwords({salt: '~webtendo~'});

function getRoomId(seed) {

return hasher.hashStr(seed).toLowerCase().split(' ').slice(0,2).join('-');

}

io.sockets.on('connection', socket => {

let clientIP;

if (socket.request.headers['x-forwarded-for']) {

clientIP = socket.request.headers['x-forwarded-for'];

console.log('clientIP', clientIP, 'aka', getRoomId(clientIP));

}

});

For users on the same subnet, they’ll magically get put in the same room on the game selection screen. For others, they’ll still have to type it, but they can use swype since these are normal dictionary words.

Hosting

The NPM ecosystem has come a long way in the last few years. Before, devs had to learn multiple systems to do build/deploy, like bower, grunt, etc. package.json allows simple flexible build/deploy through scripts.

"scripts": {

"start": "node server.js",

"webpack": "webpack --progress --colors --watch -d",

"postinstall": "webpack -p --progress --colors"

},

With just this and "engines", you can hook up your Github repo to Heroku and with a simple push to a branch of your choosing, it will build and deploy for you! And devs don’t have to remember all the options they want for webpack, they can just run npm run webpack and start hacking.

Games

In the initial set of games, I wanted to showcase

- Performance — lots of stuff on the screen at once with no degradation; realtime

- Secret vs public information — The controller can show you something private, while the main screen shows you what everyone knows

- Truly multiplayer — unlike e.g., Dominion, actions of other players are very important to you

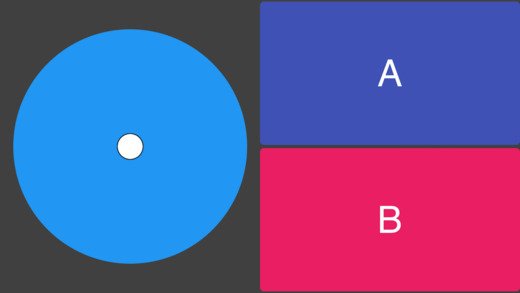

On top of that, all video game consoles have a standard controller with some kind of direction input (D-pad or joystick) and some buttons. I wanted to create one for the phone that you could use without looking at, but would still be expressive enough to make many games around. My inspiration was the original NES controller.

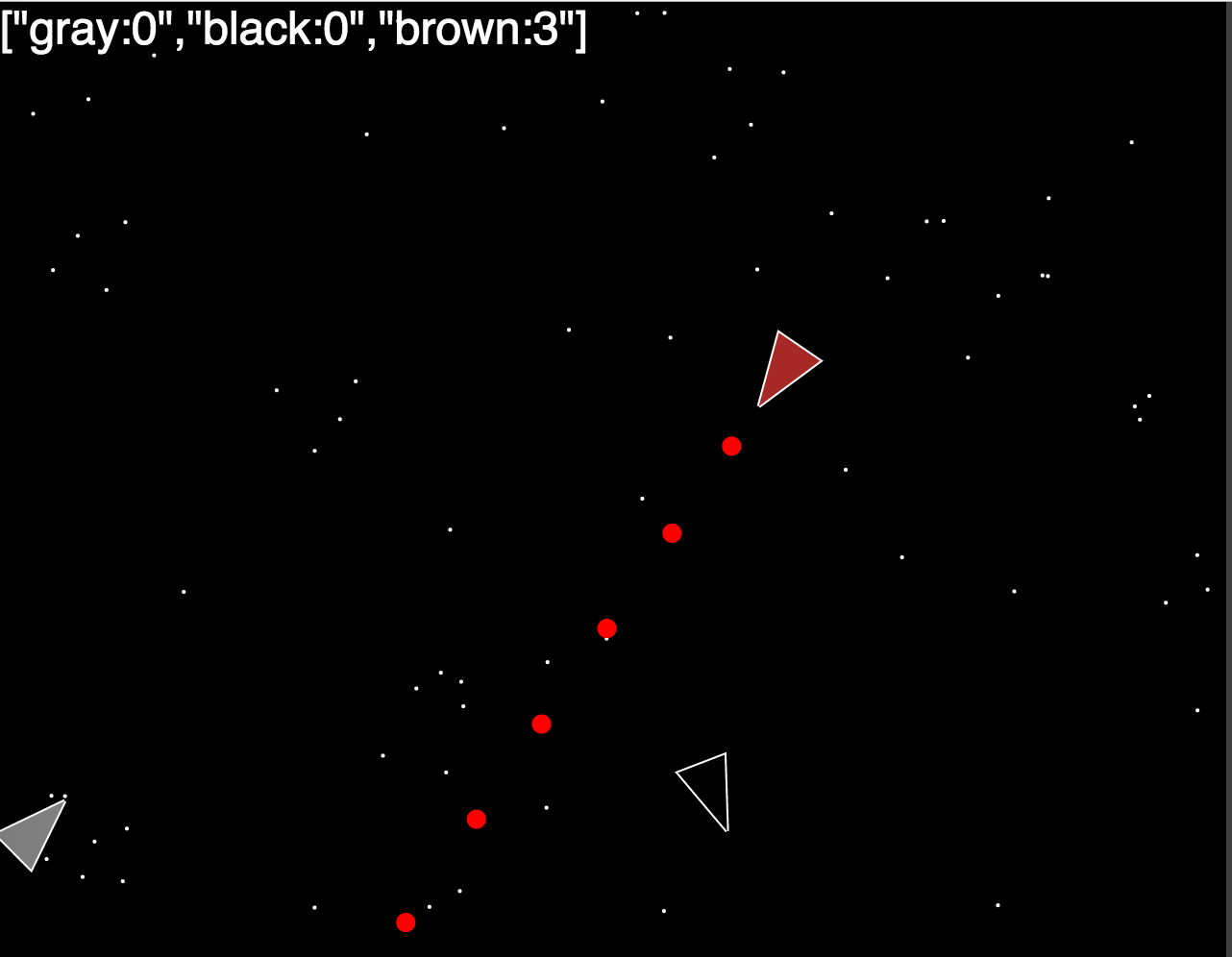

Spacewar

I actually created this by accident. I was testing the joystick and buttons and wanted a more visual way of integration testing. I looked at a few JS game frameworks, but decided to just make something from scratch to make it as simple as possible to gut and start over. By the time I had something rotating, moving around, and firing bullets, it was pretty obvious to make a space shooter. While I was at it, to load test a bit, I decided to put the stars in the background.

I actually created this by accident. I was testing the joystick and buttons and wanted a more visual way of integration testing. I looked at a few JS game frameworks, but decided to just make something from scratch to make it as simple as possible to gut and start over. By the time I had something rotating, moving around, and firing bullets, it was pretty obvious to make a space shooter. While I was at it, to load test a bit, I decided to put the stars in the background.

The only thing missing was collision detection between the bullets and the ships. Thanks to @adamreis for implementing! With many players, doing O(N2) comparisons would quickly become prohibitive with many players. Implementing quadtrees seemed like overkill, so he went the middle route and used a simple grid. Even with 8 players firing like crazy the browser still maintains framerate!

Best of all, the first time I got a bunch of friends playing this, my desired effect was achieved: everyone was shouting at each other, cheering, moaning, and generally having a great time.

Poker

Poker’s a great candidate for Webtendo. It can have many players, there’s secret (hands) and public (flop) information, the rules and accounting are complicated (how to do side pots when someone goes all-in?), and it’s annoying to set up all the chips and deal the cards.

It was also a great learning experience for @mmann, who before Thanksgiving had never written any Javascript. In spite of that, he pretty much wrote the whole thing over Thanksgiving week! It’s still got some bugs and areas for improvement I documented in the README. One of the challenges was determining the best hand. We couldn’t find an open source JS hand evaluator, so Max built one. One of the tricks was coming up with a numeric representation of the hand, so that high cards would be easy to compare without breaking encapsulation of the hand evaluation rules.

// Compute relative hand score.

handValue = 0;

for(let i = 0;i < 5;i++)

handValue += Math.pow(20, 5-i) * valueList[i + 1][0];

handValue += Math.pow(20, 6) * this.handType;

where valueList is a list of cards sorted by frequency of occurrence, then value.

When we first playtested it, we felt a little disoriented and realized it’s because with everything managed for you, the game moves fast. The first few rounds, people bet pretty arbitrarily, or were quick to go all-in. After that they sober up and start becoming more invested. It becomes more about reading people and making careful choices on how to bet. Max wrote a tool to compute betting odds that we’d like to roll directly into the game. Read about it in this Medium post.

Scrabble

Many thanks to @hyolyeng! As I developed the platform on master, I constantly broke her scrabble branch. Many of the improvements, such as not checking in the generated js bundles, were her idea. And I don’t have an iPhone, so I kept breaking that too, and she’d clean up after. Now that there are separate dirs for each game, it’s easier to develop in parallel and not step on each others’ toes.

Scrabble raised its own unique set of challenges. How to test the endgame, which only occurs after a long time? How to allow players to place their pieces, correct mistakes, etc? The controller was especially interesting. Using the default joystick-based controller, it was hard to precisely control movement. We decided to replace it with a d-pad, which was slower but much more predictable.

She implemented the board in canvas, which isn’t responsive and a little tough to maintain. A nice starter project would be reimplementing it in Vue.js.

Contribute

Ideally a community of producers and consumers will spring up around this! And even if not, I hope it serves as an example of project structure that’s suffuciently complex to support small projects. TODOs are listed in both repos below or come up with your own and send me a pull request!

Server and web https://github.com/8enmann/webtendo

React Native https://github.com/8enmann/WebtendoClient